|

UK Diving with Prima Sub Aqua is the Most Rewarding |

|

Richard Bull, Britain's Secret Seas dive supervisor for the BBC,

explains why UK diving is the most rewarding in the World. |

|

Where are the great dive sites of the world? Any diver heading for

Heathrow with his kit and his sun-cream can probably rattle off a

personal top ten. Ras Mohammed in the Red Sea would almost certainly be

there, alongside Blue Corner in Palau, the Maldives and other exotic

destinations. I bet the UK wouldn't feature on too many of those lists!

Well it would feature in mine - probably at number one. Do I hear

laughter and disbelief? I am serious, although I have to say that a

diver needs to be committed to really reap the benefits of our native

waters. I could never pretend that diving around the coast of Britain is

easy but there are many things in life the demand a little bit of effort

before the best is surrendered. That's where UK diving can be number one

- it can be the most rewarding. |

|

|

Wreck Diving in British Waters |

The Rondo

Sound of Mull

Sound of Mull

|

|

Britain has the best wreck diving in the world. Think of The English

Channel: how many sea battles have been fought over the centuries on

this strip of water? How many ships fell prey to submarines during World

War II? How many submarines themselves perished? The answer to all these

questions is undoubtedly, lots. The Channel is still the busiest

shipping lane in the world and to this day the ships are still doing

what they have always been doing - bumping into each other and sinking.

At the other end of the UK, on the bottom of Scapa Flow in the Orkney

Islands, lies a scuttled German fleet: battleships, heavy cruisers - the

lot. All around our coasts there are wrecks of mysterious historic ships

and modern wrecks about which we know a great deal. Was it really the

cook at the helm when the biggest ship ever to be wrecked in UK waters

hit the Seven Stones? |

| |

|

Basking Sharks and Cheeky Seals |

|

|

Big fish? We've got them too. The Basking Shark is the second largest

fish in the world and there are certain times of the year when these

magnificent creatures are a common sight around our western coasts. I

have encountered marine mammals all over the world but by far the most

intimate interaction has been with the seals in the Farne Islands off

the Northumbrian coast. They will want to play, and even if you don't

want to join in you can be sure that your fins will be nibbled and an

aquatic ballet will be performed right in front of your eyes. |

| |

|

Beautiful Locations |

|

|

One of the joys of a diving trip is often the beauty of the location,

whether it is a desolate Arabian desert or the lagoon of a Pacific

Island. But let me speak up for Britain. The Farne Islands are a short

boat trip from the mainland and as you approach them you witness a

forbidding, sparse beauty that reminds you you're alive. Still, you

wouldn't want to be out here in a North Easterly gale! The bird life is

stunning; from the golden plovers to the gannets and the terns. Last

time I was in the Farnes a white tailed sea eagle sat perched on a stone

tower monitoring our arrival. Don't get me wrong, I like the odd palm

tree, but the magnificence and majesty of the natural world that

surrounds some British dive sites is truly inspirational. |

| |

|

Where the Tropics meets the Arctic |

|

Britain is positioned where the weather and seas rising from the tropics

bumps into the weather and seas that descend from the Arctic. The

weather here is very unpredictable, and this is partly responsible for

the great diversity of our underwater life. I am not a marine biologist

but I am convinced that I see as many different animals and plants on a

UK dive as I have done in any far flung resort. It's not "In your face"

like it is on a coral reef and you do have to keep your eyes open - but

it is all there. |

| |

|

Choosing the Correct Gear for British Diving |

Forget the easy-to-get-on, don't-know-you've-got-it-on, very thin

shortie wetsuit that's so popular in the Tropics. A dry suit with a

thermal undersuit is the order of the day for most UK diving - and this

is going to be cumbersome; especially as it's going to require more

weight to get you under the water. Our diving is very dependent on tides

but fortunately these are predictable and with a little bit of forward

planning they need not be a problem. If you are going to dive all year

round (some of my best British diving experiences have been on very

still, crystal clear days in the middle of winter) then you are going to

have to wrap up for the boat journey. Be well supplied with flasks of

hot drinks.

Britain demands a bit more from the diver but if you want big fish,

fantastic sea-life, spectacular scenery (above and below the water),

historic wrecks and much more then it's all on our doorstep.

UK diving? For me it is the most rewarding diving in the World. |

| |

| |

|

British Sea Creatures |

|

By Tooni Mahto (Marine Biologist and Britain's Secret Seas presenter for

the BBC) |

Our small selection of islands that make up the British Isles are

regularly celebrated as a centre for wonders of both the historical and

natural kinds, most of which happen to be on terra firma. But get

underwater and you're up close to the real stars of the show, and I

don't just mean the big things like basking sharks, killer and minke

whales, common and bottlenose dolphins, not to mention the grey and

common seals and myriads of seabirds. If you're looking for fantastical

peculiarities however, you need to down-size and accept that having a

spine could be over-rated - evolution has resulted in some gems that

just happen to be on the backbone-less side of the evolutionary

spectrum.

So I thought I'd take you on a brief walk through the marine realm's

taxonomic oddities. It's not all limpets and barnacles you know. But

even the limpets and barnacles have hidden secrets to reveal. |

| |

|

Plankton |

|

|

Some of the most wonderful in their weirdness are also the smallest - if

just a single member of the planktonic community was blown up to human

sized, it would be the best-known eccentric creature on our planet. As

it is, a microscope is generally required to fully appreciate the ugly

majesty of some of these little bugs. Most of the species that attach to

the bottom of the sea have larvae that drift in the water column, and

there appears to be no physiological relationship between a larva and

what it will eventually turn into - the caterpillar/butterfly

equivalent. |

| |

|

Echinoderm |

|

|

Echinoderm larval appendages make them look like space pods set to land

on some far distant planet, and from head-on, barnacle larvae look like

disembodied horned and hairy cat-heads, but when they eventually weld

themselves to the rock, they morph into recognisable barnacles that (to

scale) have the largest penises in the animal kingdom. How else are you

going to pro-create if you're stuck to the floor and your nearest hope

to project your genes into the future is similarly adhered? |

| |

|

Copepods |

|

|

Some members of the plankton are lifers. Copepods cruise the shallows

for their entire existence; these transparent, elongated bed bugs with

frills are world-class, predatory speed machines, shooting around at

about 500 body lengths per second. Admittedly, most are less than 1mm

long, but there are few other creatures on the planet that can achieve

those kinds of speeds. |

| |

|

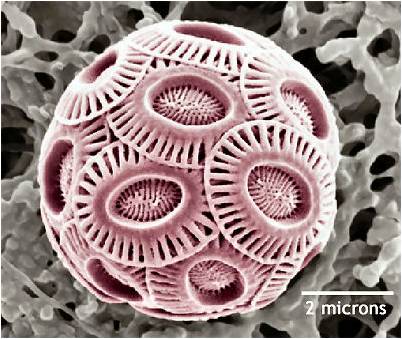

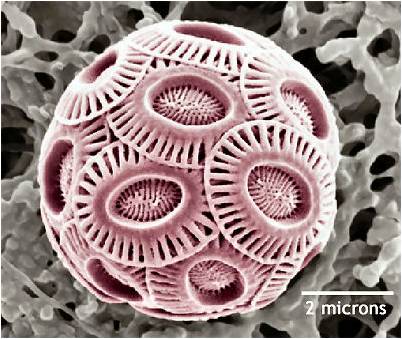

Coccolithophores |

|

Coccolithophores are tiny calcareous members of the plankton, but so

beautifully tessellated they look like an Escher design. Collectively, a

coccolithophore swarm can be seen from space as a creamy psychedelic

swirl in a blue sea, which is a timely reminder of the massive

importance this biomass of microscopic beings has to our planet -

they're food for bigger beasts, but also a sink for our excess

atmospheric carbon and the algal component produces about half of the

oxygen in our atmosphere. Never under-estimate the power of plankton.

|

|

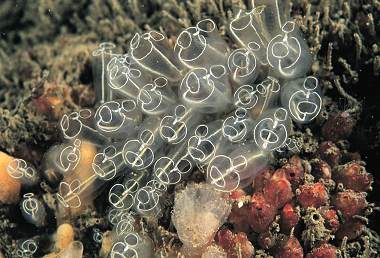

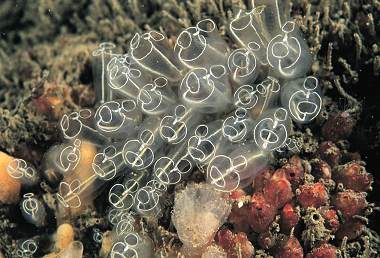

Sea Squirts |

|

| One of the strangest groups of creatures of all is the sea squirts.

Their comical title belies the fact that although they are still

invertebrates, they actually belong in the same phylum as we do - the

chordata. Take, for example, the baked bean sea squirt. Looking like,

well, a baked bean with two tubes sticking out of it, its larval phase

has a notochord, the primitive back bone that makes these filter feeding

invertebrates one of our closest marine relatives. After getting into

the 'nearly a vertebrate club' during it's juvenile stage, it performs a

volte face into true backbone-less existence attached to the sea floor,

and then spends its existence inhaling seawater, exhaling seawater,

inhaling, exhaling... you get the picture. |

| |

|

Molluscs |

|

|

If pressed to choose a favourite phylum, and it has to be said that

hasn't happened up to this point, I would have to go with the molluscs.

Who can resist the strange charms of an iridescent cuttlefish, a bulbous

octopus or a bug-eyed squid? They all glisten with certain intent, as

though they know what you're thinking. Mind readers they may not be, but

intelligent they are - although animal 'intelligence' is a hotly debated

topic, octopuses that can use tools, figure their way out of mazes and

are master escapologists and rate higher on the intellectual scale than

many Homo sapiens I have come across. In fact those in the cephalopod

class are given 'honorary vertebrate' status in the UK, meaning they're

afforded the same legal protection as a vertebrate animal. Most species

are the ultimate masters of disguise, spotting them whilst diving always

proves tricky, but a flicker of movement gives them away and you can

watch a cuttlefish manoeuvring like a stealth bomber, the tiniest ripple

of its mantle turning it to any angle, until it shoots off, powered by

water fired jet propulsion. I've often envied their millisecond swift

ability to change colour and texture. Just imagine shifting from zebra

stripes to glitter ball and the effect that would have, hence the mating

ripples of most cephalopods tend to be rather dramatic. Who can ever

tire of beings that have blue blood and four hearts? |

| |

|

Limpets |

|

|

Even limpets are pretty marvellous. I have always been touched by the

idea of a limpet returning to it's home-scar at the end of a long forage

session, to its own comfortable rock depression, nestling down like an

old man into a well loved armchair. Although a limpet's carved rock face

is the line between desiccation and living to graze another day. Once

upon a time, Victorian scientists marched along beaches and expostulated

theory as fact, deciding that limpets navigated according to the angle

of the sun and moon, the polarization of light and recognition of the

undulations of the rock. Impressive for something that on first glance

appears so conically basic. As it turns out, they follow chemical clues

left in their slippery trails, but they are specific enough to be able

to pick out their own slime from all the other limpets that are busily

going about their business, like using your sense of smell to navigate

through London. |

| |

|

Curious creatures |

|

It would be a very long read indeed to go into all the peculiar species

around our shore, so I shall end with the most curiously named critters

I could find. There's the sea hare that's more of a tortoise at cruise

speed; with an internal shell wrapped in soft undulations of tissue,

they're bizarre horned molluscs that take on the colour of the algae

they eat. There's the sea mouse that is actually a hirsute worm, and

whose genus name, Aphrodita, is inspired by the Greek Goddess of Love,

Aphrodite, although looking at them the question 'Why?' does seem valid.

The bloody Henry starfish is a deep, sanguine red starfish that inverts

its stomach to digest its food outside of its body. Then there's the sea

potato that is an urchin and the sea gherkin that's a sea cucumber that

can shift its skin structure from gloopy flaccidness to the sausage-firm

at a moments notice. The elaborately entitled By-the-wind-sailors are

colonial organisms, with polyps making up a hard disc that sits above

the water and catches

the wind, whilst propelling stinging tentacles to wreck predatory havoc

on unsuspecting plankton. Their cousin, the Portuguese man o'war,

employs the same eating tactics, but it floats on a large bubble topped

with a purple mohican and has 20-metre long tentacles dangling ominously

below. Both species are warmer water inhabitants, but an inhospitable

wind results in mass standing's on the west coast.

British seas are the most magical of locations, whether you're by the

sea, on it or in it. The diversity of differences never fails to astound

me, and every time I go on the hunt for another peculiar beast I never

am left wanting. We have an astonishing array of marine wildlife of all

sizes, shapes, curious foibles and incomprehensible forms, and it's up

to us to ensure there are safe havens for them all, from basking shark

to barnacle larva. |

| |

Sound of Mull

Sound of Mull